Growing Velvetleaf Blueberry From Seed

Velvetleaf blueberry, also known as velvetleaf huckleberry is a low wild fruit bearing shrub, native to North America. It's noted for it's soft leaves consisting of fine hairs, a great identifying feature.

These wild berries can be found along forest paths, often in the understory or edges of mixed or conifer dominant forests. Picked right off the bush, the berries are tasty and highly favourable for both humans and animals.

Though foraging is a great way to discover and create a connection with this wonderful plant, they can also be propagated and grown for personal enjoyment in your own food forest, or native plant garden. In this article we will talk about gathering the seeds and growing them from start to finish.

Collecting the Berries

Berries can be collected in late summer (August, here in northern BC). They're not always the most obvious to detect, but easy enough once you become familiar with them and are actively looking. I've seen them on gravelly slopes, along forest paths, in rich soils of understories, and in open areas of inner forests. Some indicator plants they often grow near are thimbleberry, bearberry, raspberry, juniper, various conifer trees, and underneath sands of lodgepole pine. These are places of more acidic soils where there's good drainage.

Processing the Berries for Seed

Once collected, they'll need to be processed to remove the fruity flesh and get separate the seed inside. One method is to mix the berries with water and use a blender to juice them. This is the best way I know of if you need to get it done quickly, but while it does work there is chance of some of the berries being damaged in the blending process. The other good option is to ferment them first them macerate by hand. Simply put them in a ziplock bag with some water and let it sit for a couple of weeks. The berries will ferment and soften.

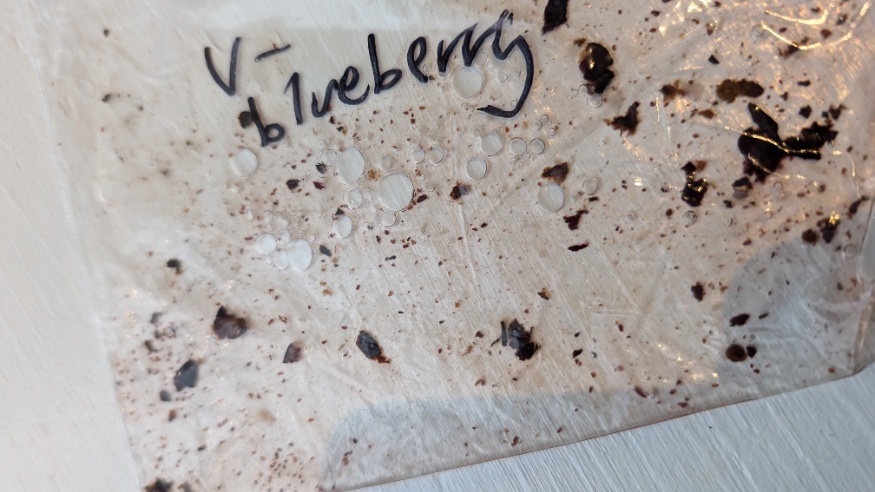

Mash them up then dilute the mixture with water. Viable seeds should sink to the bottom. Pour off the floating material and repeat until you're left with mostly seed.

As you can see, the seeds are tiny, all these seeds are from just 4 berries.

Pour off the water and allow the seeds to dry on a paper towel for 24 hours.

Stratifying

They'll need cold weather exposure to break their dormancy. This can be done by either planting them outdoors in a pot or tray in the fall, or by the bag method: mix the seeds with some sand or perlite and place in a ziplock bag. Moisten it a little with a bit of water (not too much), then refrigerate or place outside for at least 3 months.

Soil Preparation

I should note that blueberries need acidic soil to do well (between 3.8 and 5.5) and should have some organic matter. A soil mix of mostly Pete or sifted pine bark would due nicely. It would be good to do a PH test either way if making your own soil mix since Pete of different brands aren't always acidic enough. If that's the case you may need to amend it with elemental sulphur to lower the PH and it needs to be done months before you use it. You could for example use a mix of 40% pine bark, 30% Pete, 30% sand and add sulphur if needed. You can also optionally mix in a bit of compost, just make sure to test that it doesn't raise the PH too much since compost is usually around neutral.

Planting

Come early spring if you did the bag method, spread the mixture on a planting tray or pot (sand included) in part shade. Of course If you planted in the fall, they're already there. Planting depth should be just below the surface since the seeds are quite small. Keep them moist and no need to apply heat. They should come up in about 1.5 to 3 months. It will take some patience and Like many other native plants, they won't all come up at the same time. It can be a bit sporadic and once you think they're done another comes up! Watch for them; they start off quite small, the green to reddish leaves will appear, held by a zig-zaging stem.

Transplanting

Once the seedlings are small but seem big enough to handle (have a few pairs of leaves) they're ready to transplant. Pluck them out with the assistance of a butter knife, being careful not to damage the roots too much. Transplant them into their own soil block, pot, or just space them out so they can grow without competition. Again, it will take patience as they grow slowly. This was all I got out of the first season of growth from these little guys and it will need three season before fruit can be produced.

Though it's possible to propagate them from cuttings I still find seed to be the best and most satisfying way for the majority of native plants I've tried growing. Seedlings end up with better form, root development, biodiversity, and larger quantities than with cuttings or divisions. This article just covers one method that seemed to work for me. I wish you success in trying this yourself and perhaps finding better ways!